After talk of the so called "credit crunch" gave way to optimistic comments about the "green shoots" in the economy, events in Greece caught the bourgeois commentators unaware. Now the world economy has once again been plunged into chaos and uncertainty as the governments of Europe try to contain the fall-out from the near-default of Greece and it is the workers who will be presented with the bill.

“To the toiling masses of Europe it is becoming ever clearer that the bourgeoisie is incapable of solving the basic problems of restoring Europe’s economic life.” (Trotsky, On the United states of Europe, 1923)

The stock markets of the world are in turmoil. The falls on the stock exchanges are a warning that the economic revival is in danger. The extreme volatility of the market over the past fortnight reflects a fundamental lack of confidence. All the lights are now flashing red.

The immediate cause of the panic is the crisis of the euro. This is ironic. Not long ago they were talking about the euro as a rival to the U.S. dollar as a global reserve currency. Now the convulsions of the euro are driving the world's stock markets down and raising fears that the world is about to fall back into slump.

The immediate cause of the panic is the crisis of the euro. This is ironic. Not long ago they were talking about the euro as a rival to the U.S. dollar as a global reserve currency. Now the convulsions of the euro are driving the world's stock markets down and raising fears that the world is about to fall back into slump.

The once prosperous euro zone is now teetering on the edge of a terminal crisis. The markets believe that the weaker euro zone countries will not be able to take the necessary action to reduce their deficits. The fears over the Greek debt problems have rapidly turned into fears over Portugal and Spain. Only by injecting huge funds from an emergency fund can the European bourgeoisie shore up the shaky edifice.

The global financial crisis of 2008 was related to sub-prime mortgages, but now the crisis is related to what one might call sub-prime government debt. In the past, the bonds of European countries were considered to carry virtually zero risk. But now sovereign default in one of the world's core economic areas has become a serious threat. The Economist put it like this: 2008 will be remembered as the year when the banks defaulted; 2010 will be remembered as the year when governments defaulted.

Europe’s troubles can lead to a general crisis of world capitalism. On Monday May 24, Washington Post carried a very interesting headline: “One false move in Europe could set off global chain reaction”. That adequately sums up the situation. The situation is so fragile that any small incident: a missed budget projection by the Spanish government, the failure of Greece to hit a deficit-reduction target, a drop in Ireland's economic output – could set off a chain reaction that could lead to a global slump.

The conclusion of the article is striking: “the future of the U.S. economic recovery in the hands of politicians in an assortment of European capitals”. This is most revealing. It shows the extremely fragile and unstable nature of the economic recovery, which finds its reflection in the extreme nervousness of global markets. Almost anything can cause a sudden collapse of “confidence”. Credit markets worldwide could suffer gridlock, throwing the world economy back into recession. The euro crisis is only the tip of a very large iceberg, and as with a real iceberg, the part you see is frightening enough, but the hidden part is what is really deadly.

In a distorted way, the nervousness of the markets is a reflection of the growing awareness of the bourgeois that the economic crisis will lead to a sharp revival of the class struggle everywhere. The question is simply stated: will governments be able to force the workers to accept huge cuts in the public sector budgets in the interests of saving capitalism? The spectacle of workers taking to the streets in Greece, Portugal and Spain has already given them an answer that they did not want to hear.

The crisis in Greece is only the accident through which necessity reveals itself. In Greece, the chain of European capitalism has broken at its weakest link. But there are several other very weak links. Even if they find a temporary solution to the problems of Greece, the fear that the contagion will spread to Portugal, Spain, Ireland and Italy. And Britain, though not part of the Euro Zone, will not be far behind.

Effects of globalization

At bottom the crisis is a manifestation of the fact that the productive forces on a world scale are coming into contradiction with the narrow limits of private ownership and the nation state. Like the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, the bourgeoisie has conjured up forces it cannot control.

In a sense, the bourgeoisie is the victim of its success. The capitalists attempted to overcome the limitations of the nation state by increased exploitation of the world market. After the collapse of the USSR, two billion people joined the capitalist world market. The entry of China, Russia, Eastern Europe, and the increased participation of India, provided them with vast new sources of markets, investments and raw materials.

However, dialectically, everything is turning into its opposite. The process has reached its limit. Globalization now manifests itself as a global crisis of capitalism. The factors that previously served to push the world economy up are now combining to push it onto a vicious downward spiral. We saw something similar in 1997 and 1998 when the East Asian financial crisis spread rapidly through Thailand, Indonesia, South Korea and other nations. Now Europe is facing the same prospect.

It may be argued that Greece, Spain, Portugal and Ireland represent only about four percent of world economic activity. But once the dominoes start to fall, the effect can pass rapidly from Greece to Portugal and Spain, then to Ireland and Italy, then Britain. Confidence in the euro would collapse, causing chaos in world money markets that would end in a new crisis in Wall Street. In the words of Cornell University economist Eswar Prasad: "the debt crisis and its ripple effects are bad news for all corners of the world".

The Washington Post continues:

“Inside the euro zone, banks are intimately linked, with a web of investments and cross-country bond holdings that could be a main vector for financial ‘contagion,’ with a default in one country weakening banks elsewhere.”

Europe in crisis

Drawing by Latuff.The crisis is pushing Europe, and its nation states, into dangerous and uncharted waters. There were growing fears about the exposure of banks to European governments and private borrowers. If nothing was done, European governments would have been faced by the same fate that was suffered by Lehman Brothers. Greece could be on an inexorable path towards default.

Drawing by Latuff.The crisis is pushing Europe, and its nation states, into dangerous and uncharted waters. There were growing fears about the exposure of banks to European governments and private borrowers. If nothing was done, European governments would have been faced by the same fate that was suffered by Lehman Brothers. Greece could be on an inexorable path towards default.

By May 7th, yields on the weaker euro-area countries’ government bonds rose sharply, as the markets showed their muscle. There is a real threat that foreign financing for these countries would cease altogether. The bond markets’ nervousness indicates that the investors are quite prepared to see whole nation states go under. They are firm believers on the old Chinese proverb: “What do you do when you see a man falling? – Give him a shove!”

It is true that all euro-area countries have an interest in avoiding a default. If Greece goes under, the markets’ attention would immediately pounce on Portugal, Spain, Ireland and Italy. Confidence in the euro would plunge. Yet the German bourgeois do not like the idea of paying the debts of “profligate” countries.

On May 2nd euro-zone governments and the IMF set out the terms of a €110 billion ($145 billion) rescue for Greece. That was far more than had previously been promised but it was not enough to settle investors’ nerves. Stockmarkets in Europe and America slumped on May 4th and fell again the next day. Greek bonds continued to trade at the level of junk bonds.

Caught on the horns of a dilemma, the European bourgeoisie did not know what to do. The policymakers have been accused of doing too little, too late. But in reality, whatever they did would be wrong. In the end Germany and the European Union were forced to act to save the euro zone. In the early hours of May 10th finance ministers, meeting in Brussels, agreed on an emergency plan to prop up the euro zone. The main element is a “stabilization fund”, worth up to €500 billion ($635 billion). Of this, €60 billion is to be financed by the sale of EU bonds.

The fund is to be supplemented by up to €250 billion more from the IMF. In addition, the European Central Bank (ECB) said it would purchase government bonds to restore calm to “dysfunctional” markets. It will offer banks unlimited loans at a fixed interest rate. Yet again the governments are handing out billions to the banks to prevent a collapse. But in the first place, there is no guarantee that there will not be such a collapse, and in the second, who will pay the bill for these huge sums?

The financial markets’ initial reaction was naturally euphoric. How could the sharks not be euphoric at the prospect of further billions of taxpayers’ money being shoveled down their greedy gullets? Germany’s stock market closed more than 5% higher on May 10th. France’s main index went up by almost 10%: big French banks are heavily exposed to Greece, so they also stand to benefit handsomely.

However, this euphoria soon gave way to a more somber view. The market knows that the whole thing has been hastily cobbled together, and there is no guarantee that it will work for long. The package, despite its impressive scale, only buys time for Greece and other vulnerable troubled governments to cut their budget deficits and to improve their lost export competitiveness. If that is not done, there will be an even worse crisis in the euro zone in a few months.

National conflicts

A strained relationship. Photo by the office fo the Prime Minister of Greece.The appearance of European unity was in reality an illusion. Behind the façade of unity and solidarity, all the nation states jealously guarded control over their national interests and their national banking systems. These divisions have been cruelly exposed by the present crisis.

A strained relationship. Photo by the office fo the Prime Minister of Greece.The appearance of European unity was in reality an illusion. Behind the façade of unity and solidarity, all the nation states jealously guarded control over their national interests and their national banking systems. These divisions have been cruelly exposed by the present crisis.

The parsimonious spirit that lies behind all the talk of an “international rescue” is shown by the long delays in approving the plan, which even then was further delayed by failure to agree on details such as the interest rate to be charged for access to funds. And immediately after the deal was signed, the conflicts between the national governments began.

Germany is insisting that the money will be raised and controlled by governments, not bureaucrats in Brussels. They do not want huge amounts of money being handed out without close monitoring. In other words, the money will be given to Greece with the strictest monitoring and control. Britain said it will not sign up to it.

Jean-Claude Trichet, the central bank’s president, was accused of “caving in to political pressure to help out spendthrift governments”. Axel Weber, the head of the Bundesbank, Germany’s central bank, who may succeed Mr Trichet when he steps down next year, openly criticized the ECB’s conduct in the pages of Börsen-Zeitung, a German financial newspaper. In his defence, M. Trichet maintains that the central bank was “fiercely and totally independent”, a statement that not many people believe these days.

A speech made by Merkel during a rowdy session of the German federal parliament made matters worse. She said that "the current crisis facing the euro is the biggest test Europe has faced in decades," and: “If the euro fails, then Europe fails". The already panicky markets plunged again.

Germany took a unilateral decision to ban the short selling of EU government debt and banks. The move was taken because of the German Chancellor's increasing desperation ahead of last Friday's vote on the euro bailout. The opposition MPs and increasingly her own coalition members are becoming increasingly angry. Merkel had to do something to prove that Germany was not simply writing a multi-billion euro cheque from the taxpayer to bail out Greece and others. She was trying to show that Germany was taking steps to defend itself.

This was no more than a mild attempt to control speculation. It has no chance of success. But the markets want complete freedom to pursue their predatory activities. The move wiped billions of euros off the value of shares and drove the single currency down to a four year low. It infuriated Germany's European partners, who had not been consulted. There were unprecedented public recriminations from Christine Lagarde, the French finance minister. There were naturally loud protests from London (both Labour and Tories were agreed), reflecting the completely parasitic character of British capitalism's reliance on finance capital.

Hypocrisy of German capitalists

The underlying sickness of European capitalism is reflected by the feverish movements of the stock exchanges. The financial world is being shaken by rumors of the possible collapse of the euro zone. All the official denials have not helped to calm the jittery nerves the markets. In this mood of panic, the bourgeois seek to find someone to blame. The Germans blame the Greeks. The Greeks blame the speculators. The French blame the Germans.

Increasingly, the finger is being pointed at Berlin. Germany, which was the engine of growth for the whole EU, its banker and de facto leader, is now the target of all the pent-up anger and frustration of its partners. Why are the Germans so stingy? Why did Merkel not do more to help Greece earlier? At a recent meeting of European leaders it is said that President Sarkozy threatened to leave the euro zone if Berlin did not help Greece

The criticisms of her neighbours do not go down well in with Berlin. The prostitute press in Germany and other countries are trying to portray the situation as “Europe helping lazy Greek workers.” That is a lie. This crisis was not brought about by the workers of Greece or any other country. It was created by the voracious and reckless actions of the bankers and capitalists of both Greece and the rest of Europe. And the present “rescue plan” is a plan to rescue, not Greek workers, but the bankers of Germany, France and other countries who own most of the debts of Greek capitalism.

The public displays of moral outrage in Germany reek of hypocrisy. German capitalism benefited more than any other from the introduction of the Euro. The German capitalists enjoyed a privileged position in the years of boom. Their exports invaded every market, taking advantage of the fact that weaker economies like Greece, Spain and Portugal, could no longer devalue the currency to protect their national market. German banks were happy to make profits out of lending to Greece, Spain and Eastern Europe. They made a lot of money then, but they are not prepared to accept losses now.

Germany’s dilemma

The problem is that, in the end, somebody has to pay the bills. Merkel managed to push through the euro zone-wide bail-out mechanism on May 21. But opposition among German voters is growing and it is spreading to Merkel’s coalition partners and political allies. “Once again, we’re Europe’s fools” was how Bild, the influential German newspaper, greeted news of the euro rescue plan. In the latest polls, 47 percent of Germans are in favor of returning to the deutschmark. In a crucial state-level election May 9 Merkel’s governing coalition was heavily defeated. This is a sign of mounting dissatisfaction with her Christian Democratic Union and its coalition ally, the Free Democratic Party.

The weaker members of the rich man’s club, known as the “Club Med” economies, currently have a 3 trillion euro mountain of debt and their ability to service it is in doubt. The “markets” are nervous about this. That is to say, the bankers are nervous, because they fear that they may not get their pound of flesh. That means, in the first place, the German bankers. Exposure of German banks to Club Med debt may be as much as 500 billion euros. Thus, despite all the huffing and puffing in Berlin, what is being discussed here is not aid to Greece, but aid to the German bankers and their European partners in crime.

From the point of view of German capitalism it was a case of “damned if you do, and damned if you don’t.” If they provided Greece (and other weak euro zone economies) with money, they would have trouble at home, and anyway there is no guarantee it will succeed. If they refused, a Greek default would have a domino effect throughout Europe and on a world scale, which would pull Germany down with everyone else. Therefore, Merkel was forced to swallow hard and approve a huge bailout.

At some point, Germany may conclude that further bailouts are just throwing money into a bottomless pit. At that point, Germany may decide to cut its losses. Germany may decide that the ECB should ignore its rules and purchase the debt of the weak euro zone governments by the simple device of printing money (“quantitative easing”). The euro zone, including Germany, would be paying for it this with the weakening of the euro and higher inflation.

The Germans complain a lot, but they overlook the fact that the euro zone provided Germany with considerable economic benefits. Since the euro was adopted, unit labor costs in Club Med have increased relative to Germany’s by approximately 25 percent, further improving Germany’s competitive advantage. Its neighbors are unable to undercut German exports with currency depreciation, and German exports have benefited. The result has been a massive €110 billion (2007) current account surplus for Germany towards the rest of the Euro-zone. That means that Germany exports €110 billion more to the Euro-zone than it imports, which is paid for by massive lending from German banks. For German capitalists this was of tremendous benefit in the short-run but in the long-run it is completely unsustainable.

In order to revive the deutschmark, Germany would have to reinstate the Bundesbank, withdraw its reserves from the ECB, print its own currency and then re-denominate the country’s assets and liabilities in deutschmarks. This would be difficult, but not impossible. The other members of the euro zone would face far greater difficulties if they wished to return to their old currencies.

However, since German banks own much of the debt issued by Club Med, the losses caused to Germany by a break with the euro zone would be far greater than remaining within the euro zone and financially supporting it, at least for the time being.

Greece – the sick man of Europe

Greece joined the Euro in 2001. At that time German capitalism was puffed up with its own importance following reunification. The moving of its political centre to Berlin in the heart of Europe symbolized its unlimited ambition to become the Master of Europe. Under these conditions the Imperial Master graciously accepted the accession of Greece as a further step towards consolidation of German domination of the Balkans, which began with the German-inspired intrigue to break up Yugoslavia.

However, Greek capitalism is the weakest of several weak links in European capitalism. The Greek bourgeoisie – one of the most corrupt and reactionary in Europe – thought that it was being very clever when it joined the European rich man’s club. Like the frog in Aesop’s fable, it blew itself up to an enormous size, and then it exploded.

Even in 2001, the real weakness of Greek capitalism ought to have been clear to a blind man. It was graphically expressed in the huge deficits in the current account, budget and public debt. As long as the boom continued, Karamanlis could comfortably maintain himself in power for four-and-a-half years. He easily won two elections. The Greek economy appeared to be healthy, with growth averaging over 4% a year up to 2007.

The tourists were streaming in, construction was booming as a result of the 2004 Olympics. Greek ship-owners were making record profits from China’s export boom; Russian oligarchs were buying expensive land on Aegean Islands. There were subsidies from the European Union. Last but not least, Greek membership of the Euro seemed a guarantee of future prosperity.

But the global economic crisis cruelly exposed the underlying weakness of Greek capitalism. As a direct result of the adoption of the euro, the Greek economy has lost competitiveness. Many Greeks are underemployed. This affects the youth in particular, with a sharp rise in youth unemployment and a reduction of openings in education. The unemployment rate for young graduates in Greece is 21%, compared with 8% for the population as a whole.

But the global economic crisis cruelly exposed the underlying weakness of Greek capitalism. As a direct result of the adoption of the euro, the Greek economy has lost competitiveness. Many Greeks are underemployed. This affects the youth in particular, with a sharp rise in youth unemployment and a reduction of openings in education. The unemployment rate for young graduates in Greece is 21%, compared with 8% for the population as a whole.

The growing mood of discontent that was seething beneath the surface was shown by the violent youth protests after Alexandros Grigoropoulos, a 15-year-old schoolboy, was shot dead by a policeman in December 2008. The murder triggered five nights of riots. The protests quickly spilled into the main streets of Athens, and thence across the country. There were violent clashes with riot police and tear-gas filled Syntagma Square. Groups of youths burned cars, broke shop windows decorated for Christmas and tossed in petrol bombs.

These demonstrations were on an unprecedented scale, resembling an uprising of the youth. Demonstrators attacked police stations and public offices in a dozen cities, causing damage estimated at more than €100m ($130m). Hundreds of school students battled with police after the teenager’s funeral. Others threw stones at policemen on guard outside parliament, shouting “let parliament burn”. This was already a warning to the ruling class. It showed the pent-up anger of Greece’s youth, which was only an extreme expression of a general discontent in Greek society.

Throughout history, every revolution has been anticipated by a movement of the youth – particularly the students, who are a sensitive barometer that reflects the buildup of contradictions and tensions in society. This was the case in Russia in 1901 and in Spain in 1930. In both cases, the demonstrations of the student youth were a warning of the revolutions of 1905 and 1931.

Kostas Karamanlis. Photo by New Democracy.The protests caused paralysis of the authorities. The right wing government of Costas Karamanlis, terrified of provoking an even bigger movement, was unable to impose a curfew or order mass arrests. The memory of the military dictatorship in the 1970s was too fresh in people’s minds. Attempts to arrive at a consensus between political leaders on how to quell the unrest quickly broke down. On December 10th there was a 24-hour strike by public-sector unions, despite Karamanlis’s appeal for it to be cancelled.

Kostas Karamanlis. Photo by New Democracy.The protests caused paralysis of the authorities. The right wing government of Costas Karamanlis, terrified of provoking an even bigger movement, was unable to impose a curfew or order mass arrests. The memory of the military dictatorship in the 1970s was too fresh in people’s minds. Attempts to arrive at a consensus between political leaders on how to quell the unrest quickly broke down. On December 10th there was a 24-hour strike by public-sector unions, despite Karamanlis’s appeal for it to be cancelled.

These events caused alarm among the international strategists of Capital. On 11th December The Economist commented:

“There is something weird and frightening about the sight of a modestly prosperous European country—assumed by most outsiders to have recovered from its rocky history of coups and civil strife—that is suddenly gripped by an urban uprising that the authorities cannot contain.”

The events of December 2008 led inexorably to the fall of the Karamanlis government. George Papandreou, the Pasok leader, called for a general election. “Effectively there is no government…we claim power,” he said. The Pasok gained in popularity as the support for the New Democracy melted away in a welter of financial scandals.

The Pasok government

The general election on October 4th 2009 resulted in a landslide victory for the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (Pasok) that surprised both the political observers and the Pasok leaders. This was a clear reflection of growing popular discontent. 43.9% of voters backing the party, giving it 160 seats in the 300-member parliament. The centre-right New Democracy party was shattered. It won only 33.5% and 91 seats—its worst-ever showing at the polls.

This was the biggest victory for Pasok since it first came to power in 1981. It goes against the trend Europe in the recent elections where social democratic parties have been defeated. It was a clear vote for change. The Communist Party (KKE) took 7.5% and 21 seats, while Syriza, a left-wing coalition that arose from a split from the CP, took 4.6% and 13 seats. Laos, a far-right party, increased its share of the vote to 5.6% and won 15 seats – at the cost of the ND.

Unlike his father, Andreas Papandreou, and like Blair in Britain, George Papandreou has worked to pull the party to the right. Brought up in Sweden, and educated in the USA, he enjoys friendly relations with Obama. Initially he promised stimulus of up to €3 billion ($4.4 billion) to accelerate economic recovery and above-inflation increases in wages and benefits for public-sector workers. He also promised real rises in wages and pensions to encourage Greeks to spend again. He talked of exporting renewable energy, harvested on sunny mountainsides and windy Aegean Islands, and persuading Greek software developers abroad to set up companies at home, and so on and so forth.

But these reformist dreams immediately evaporated like a drop of hot water on a hot stove. They came into conflict with the harsh reality of economic crisis, collapsing tax revenues and a soaring budget deficit. The Karamanlis government admitted that Greece had manipulated its figures to qualify for the euro in 2001. Papandreou admitted that this year’s budget deficit was not 6.7% but 12.7%.

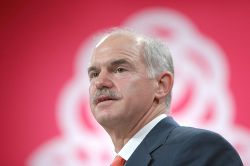

George Papandreou. Photo by philippe grangeaud / solfé communications.It is true that the Greek capitalists, with the mentality of a petty haggler in the marketplace who wishes to sell rotten fish by placing fresh ones on the top, tried to get round the problem by the simple expedient of falsifying the statistics to conceal the facts – something they are, incidentally, not alone in practicing. But sooner or later the facts become known. The source of the problem, however, was not in Athens and its faulty accounting.

George Papandreou. Photo by philippe grangeaud / solfé communications.It is true that the Greek capitalists, with the mentality of a petty haggler in the marketplace who wishes to sell rotten fish by placing fresh ones on the top, tried to get round the problem by the simple expedient of falsifying the statistics to conceal the facts – something they are, incidentally, not alone in practicing. But sooner or later the facts become known. The source of the problem, however, was not in Athens and its faulty accounting.

The problem is precisely with the mechanism of the “free market economy”, which operates with the same rationality as a herd of antelopes in the veldt. As long as the market was heading upwards, they did not pay any attention to the niceties of economic and financial soundness. But once the markets head downwards panic sets in and a stampede begins. Now that the stampeded has begun, nothing can stop it. The speculators rush blindly from one market to another in search of a safe haven. In the process, they trample the crops, demolish houses and kill anyone who stands in their path.

The markets decide

There was an old saying: man proposes and God disposes. Nowadays it would be more correct to say: Man proposes but the Market disposes. With a budget deficit almost 13% and a public debt of 125% of GDP, international investors were not impressed with Papandreou’s promises, and sent him a little message to convey their opinion. Spreads on Greek government bonds over German Bunds began to widen, and have continued to widen ever since. This is the financial equivalent of laying hold of a man’s genitals and exerting a gentle squeeze.

Papandreou wants social peace with fiscal austerity. But the two things are incompatible. Papandreou wants to avoid direct confrontation with the trade unions, but he has only two alternatives: either he defends the interests of the workers or those of the capitalists. And he has made his choice. Papandreou is compelled to cut living standards in order to placate the almighty Market, just as Agamemnon was obliged to sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia in order to placate the Gods of Olympus. However, Agamemnon ended up very badly as a result of his actions, and his successor will not end up any better as a result of his.

The Greek premier is trying to hide behind the IMF and the anonymous “international speculators” that have brought Greece to its knees. But for the millions of Greek workers who are faced with savage cuts in their living standards, these arguments do not excuse the actions of the Pasok leaders. The Greek workers hate the speculators, the IMF and the bourgeois leaders of the EU. But they cannot forgive a government that, while calling itself socialist, has so readily bent the knee to the IMF and Brussels.

Immediately, Papandreou found himself ground between two millstones. The prime minister’s promises of fiscal austerity have not convinced the markets. For every step back the reformist leaders take, the bourgeois will demand ten more. The Economist remarked: “By Greek standards Mr Papandreou has been courageous, but he should have been braver still. Ireland set the pace on December 9th by producing a budget that sharply cut public-sector wages.” And it added: “Hard times, unfortunately, demand harsh measures.” Here is the real voice of the bourgeois: stony-faced, hard hearted, and completely impervious to human suffering. All must be sacrificed on the altar of Capital!

The austerity measures approved by the Athens government were too little for the bourgeoisie, but too much for the workers. The Greek workers, following their marvelous revolutionary traditions, immediately reacted with mass street demonstrations. Feeling themselves betrayed by the government they hoped would defend jobs and living standards, the workers of Greece have taken to the streets. For months, Athens and other cities have been rocked by mass protest demonstrations. One bourgeois commentator in Britain described the situation in the following terms: “Greek workers against European bankers.” That puts it very well.

Marx wrote that France was the country where the class struggle was always fought to the finish. The same can be said of Greece. The memories of the Civil War and the bitter divisions between Left and Right, and later of the Junta and the Polytechnic uprising of 1974 are burned on the consciousness of the masses. The divisions between the classes constitute a fault line running through Greek society that can explode at any time.

The question can be put very simply: the bourgeoisie cannot afford to maintain the concessions that were forced from them in the past. But the working class cannot tolerate any further attacks on their living standards and conditions. The workers of Europe will not stand with their arms folded while the conquests of the last fifty years are systematically destroyed. The developments in Greece therefore show what will happen in every country in Europe as the crisis unfolds.

http://www.marxist.com/new-state-in-crisis-of-capitalism-part-one.htm

Au cours des deux dernières semaines, la situation en Europe a continué à évoluer de façon erratique, sinon à se dégrader. L’euro a atteint son plus bas niveau depuis 2006. Il a perdu près de 18% de sa valeur depuis décembre 2009, date à laquelle il s’échangeait autour des 1,50 contre le dollar.

Au cours des deux dernières semaines, la situation en Europe a continué à évoluer de façon erratique, sinon à se dégrader. L’euro a atteint son plus bas niveau depuis 2006. Il a perdu près de 18% de sa valeur depuis décembre 2009, date à laquelle il s’échangeait autour des 1,50 contre le dollar. Faut-il réduire le taux d’intérêt pour relancer la machine ? La solution est souvent préconisée comme une panacée. Or, elle n’aurait, dans ce cas, qu’un seul effet: réduire l’endettement des opérateurs économiques les plus endettés. Cela ne se traduirait pas nécessairement par une relance de l’investissement intérieur. Si c’était le cas, la solution serait toute trouvée.

Faut-il réduire le taux d’intérêt pour relancer la machine ? La solution est souvent préconisée comme une panacée. Or, elle n’aurait, dans ce cas, qu’un seul effet: réduire l’endettement des opérateurs économiques les plus endettés. Cela ne se traduirait pas nécessairement par une relance de l’investissement intérieur. Si c’était le cas, la solution serait toute trouvée.

A year ago the world was 18 months into the worst economic crisis since the 1930s. The economy was still in “free fall.” The investment banks and the shadow banking system had collapsed, the commercial banks were dysfunctional, and many were going bankrupt. Credit, even lending between banks, was frozen. World industrial production plunged by 20 per cent, as did world trade – a contraction only exceeded during the Great Depression. Nobody knew where the bottom was, and various catastrophists warned that there was no bottom in sight.

A year ago the world was 18 months into the worst economic crisis since the 1930s. The economy was still in “free fall.” The investment banks and the shadow banking system had collapsed, the commercial banks were dysfunctional, and many were going bankrupt. Credit, even lending between banks, was frozen. World industrial production plunged by 20 per cent, as did world trade – a contraction only exceeded during the Great Depression. Nobody knew where the bottom was, and various catastrophists warned that there was no bottom in sight.